![Interview with Wuon-Gean Ho, editor at Printmaking Today, on 9th August 2017: Thank you [for showing me your etchings in the Sausage, Dogs & Schadenfreude show]. They are brilliant. I want to show whole pages of them [in Printmaking Today]..](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/591a021d3e00bef035cff344/1498341666677-Z3W9UMKGPVXB7DGT82AJ/P6231414.JPG)

Sausage, Dogs & Schadenfreude (Don't Lose Your Head) was the title of my MA dissertation at the Royal College of Art in London. I came there after living several years in a German forest, and the writing was a product of that experience, which included being a bear for a day.

I explored the Wildermann - or Wild Man - phenomenon, which is found in many highland regions of Europe and elsewhere, as well as Anglo-German relations, conflict, decapitation, unexpected death, dogs, fate, firefighting, steel helmets, masculinity, masks, migration, mythmaking, the manufacture of paper and sausages.

Fertile matters in this time of exiteering and post Cold-War trouble.

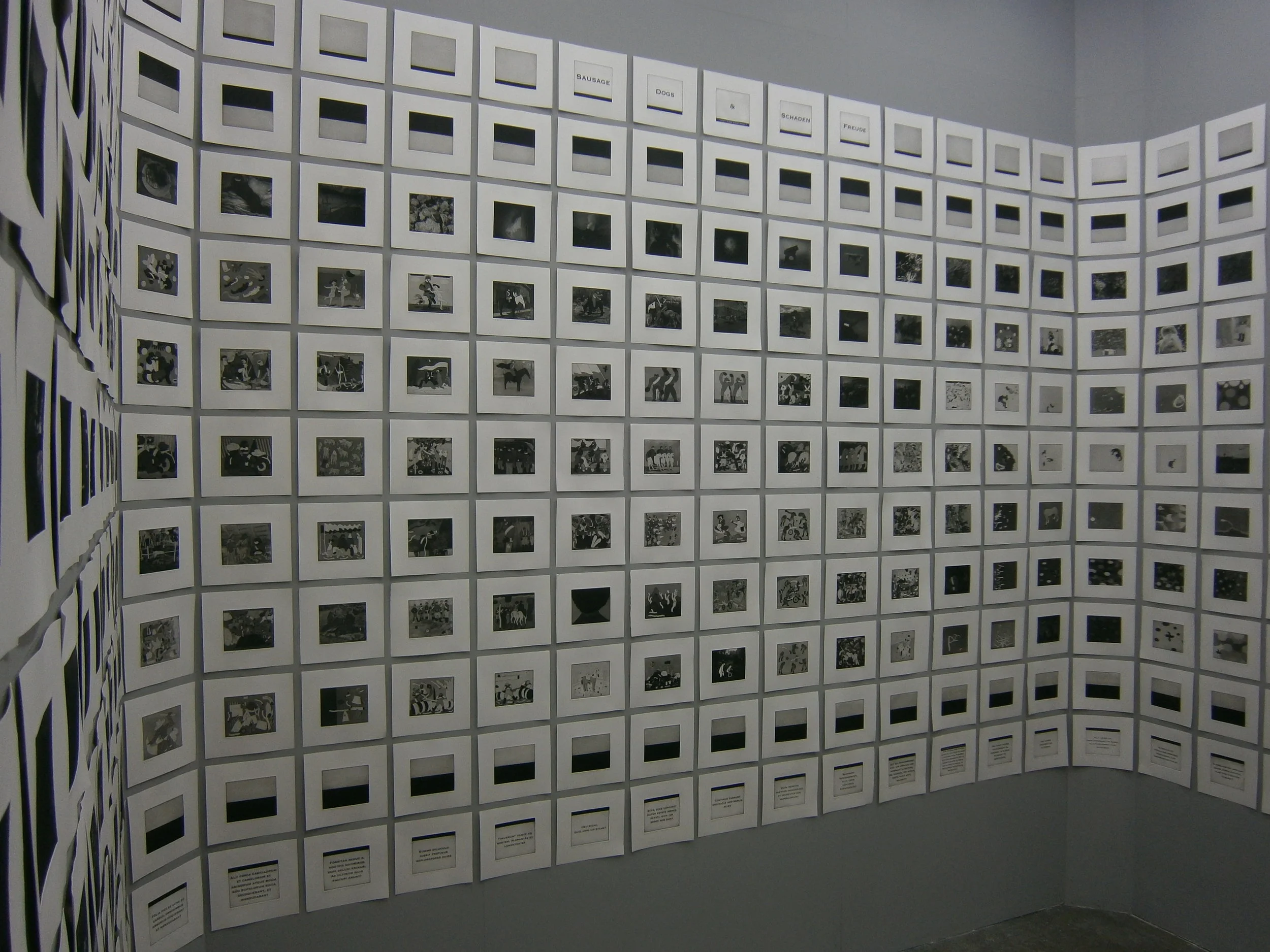

In turn, I responded to the written work with a degree show exhibition in June 2017 that included 462 etchings, a 6½ minute moving image diptych, a 53 minute sound installation, a bronze helmet and an appearance at the Private View, albeit briefly, of the Wildermann itself.

The Wildermann's bronze helmet and some of the 418 etchings from Sausage, Dogs & Schadenfreude (Don't Lose Your Head).

XXIII (no. 23 of 418)

35 texts in Latin, accompanying the images, are excerpts from the Gesta Francorum, written in bad Latin by an anonymous participant of the First Crusade almost a thousand years ago. They describe the narrative of my etchings in a language tantalisingly familiar to Europeans yet incomprehensible (unless you're a scholar of Latin, of course!). It was the first primary source I ever had to untangle for history lessons at school.

![Interview with Wuon-Gean Ho, editor at Printmaking Today, on 9th August 2017: Thank you [for showing me your etchings in the Sausage, Dogs & Schadenfreude show]. They are brilliant. I want to show whole pages of them [in Printmaking Today]..](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/591a021d3e00bef035cff344/1498341666677-Z3W9UMKGPVXB7DGT82AJ/P6231414.JPG)

Interview with Wuon-Gean Ho, editor at Printmaking Today, on 9th August 2017:

Thank you [for showing me your etchings in the Sausage, Dogs & Schadenfreude show]. They are brilliant. I want to show whole pages of them [in Printmaking Today]... There's not enough space...

You’re very kind.

It’s a veritable army of prints, all marching in formation

Yes, they are, aren’t they.

For me, they depict (in a somewhat nostalgic way) a parade of action figures, anonymized by masks and decapitation, inflated by bendy limbs and harmless googly eyes. It’s a kind of mythical mock horror story, recurring in endless combinations.

Yes, nicely observed. The figures did start as inept-ish apocalyptic superhero types riding ridiculous, sausage-shaped beasts. When I came out of the wilderness, I noticed that the Western had waned and been upped and outmaneuvered by superhero films and TV series. The hero was no longer self-reliant, thoughtful and robust, but often needy, introspective and flawed. The cowboy was dead, long-live the superhero. I’m still not quite sure of the why of this popularity shift, but it feels important.

There was indeed a narrative flow in the presentation of the work, and, yes, the viewer could work their way through it as they wished – there was no ‘correct’ path. Nevertheless, I do love a story, so I did put in a Homeric journey, or migration, beginning with landscape (photographic etchings of locations familiar to me, principally in Germany); the emergence of the figures and their beasts; their passage through the terrain and into their own, drawn, world; their encampment and preparation for an undisclosed adventure; the setting off, including farewells; the march through a drawn, volcanic landscape; a cataclysmic encounter with an invisible force; aftermath; the arrival of the detritus in a more urban photographic world; rest; a hint of preparation for the cycle to begin afresh.

On the Monday after the Friday installation deadline, I discovered all 462 prints had come loose and were lying on the floor. I groaned, but got to work putting them back up; I had photos I could refer to, but I chose to just use my intuition. When I compared the new arrangement with the original one, they didn’t match. Nuances of the narrative had changed, but the story was essentially the same. No doubt, the combination is endless.

What happens with armies, and rows of people, is the spot-the-difference activity that we participate in, comparing across and down, making connections. Do you think that is how people responded to the work?

Yes. Definitely. I like teasing as well, so sometimes you think you spot a consistent character popping up from time to time, but there will be discrepancies in the way they are drawn. Which is kind of what we do when we re-tell stories.

I spent almost every day of the show watching people look at the work. Some responded very emotionally, affected by a sense of the content, aware that each etching was its own thing, but that they connected - despite any humour - into a traumatic whole. Others seemed to be happy with just the overwhelming aesthetic effect of standing in a bright room surrounded by an enormous grid of black, white and grey. Some looked blank, but recognized the technical effort. Quite a few strolled in, blanched, spun on their heels and moved on to less taxing exhibits. (I do think it needed a bit of courage to start looking a bit harder than normal.)

Any comparisons to churches or chapels? Having said that, the [bronze] helmet looks like a tribute, or a self conscious prop from a stage set…

Churches and religion were absent from any discussion.

The helmet has a few layers to it. As archaeological relic – as if the characters depicted really did exist at some time (it bolstered their credibility). As replacement of the crappy village ‘bear’ mask of the Wildermann in Germany (but it was too heavy to be worn). As reinterpretation of the iconic German World-War-Two helmet, a fetish object to many British schoolboys and adult reenactors, and one still worn in the German fire brigade (imagine my delight at having to wear it!).

What was the soundtrack like? Did the frame around the work change it? Sketches first, or sculptures? How important was the sequence?

The moving image piece was a diptych using 8mm film taken by grandfather in the early 1940s, and my father in the 60s & 70s. I juxtaposed shared interests – the similar things they were both driven to film, though one was in war and the other in peace. My grandfather disappeared in 1945, the consequences of which set in motion a long, convoluted drama of migration and my eventual arrival in Britain.

The sound piece was a collation of noises, snippets of conversation, moments in films (war and westerns), broadcasts, strung out and intruding suddenly. Again, the topic alluded to migration and foreignness, memory and family, love and conflict. Occasionally, the screen on the wall flickered to life with home-video references to what was heard, and also a failed film version of a re-enactment of the Wildermann, with my father filming and my mother directing (I wrote the script).

All the components of the degree show were done under their own steam. I left out other components (I was also working on a series of flags, for instance).

Forget the theory, what do you tell your daughter when she sees your work?

It’s your story, too, darling.

Goya, Dix, Chapman, Rego? [What’s] your family tree [or] artistic pedigree?

Goya drew what he had to draw in the context of witnessing the Napoleonic Wars. Likewise Dix’s drawings in coping with his Great War experience. I respect the emotional response – the sincerity – even if Dix’s helmets were a bit sloppy. But he did a good ooze. I don’t do ooze.

I always had a problem with the Chapman brothers. It bothered me they were taking Goya and the Nazis and mashing the two together. Again, probably, it’s just the British obsession with World War Two. Their work leaves me cold.

I like Paula Rego. She conjures up her internal world using a concise visual language which I can relate to.

The draughtsman I most admire and who made the earliest impact on me was Georges Remi, aka Hergé, creator of Tintin. It’s all about the line. (Although I was quite shocked when I eventually saw how skittery and broken his preliminary drawings were and how much he had to tighten them.) I love containment, too. Clear borders. You might have noticed, I don’t let my tones bleed all over the place.

Is there a subconscious development to the storyline? Where are the sausage dogs?

There’s always a subconscious development. I just don’t recognize them until later, if ever. The difference here with the Degree Show, perhaps, was that because of the dissertation – and the rigorous research involved – I was more aware of the kind of work I wanted to show. More in control of the visual story. Nevertheless, although I embedded several deliberate layers of interpretation, I sense there are probably many others that have sneaked in unobserved.

Where are the sausage dogs? They’re in there, I can assure you.

How about the locations? [I can see] London Bridge.

The finale, or denouement, of the work has a more urban setting. Some of the images are in London. London is where I lived before I experimented at being German, and London is where I have now returned to.

Are there hidden poems or statements?

It’s interesting that you ask about hidden poems. All 462 etchings of the two series have a number and a title. The titles, when put together, create a text. I didn’t have time to polish this aspect – or layer – of the work, but there are passages which have a rhythm and a flow. For example:

CCLXXVIII (278) Ich Hatte einen...

CCLXXIX (279) Afterthought

CCLXXX (280) I love It here

CCLXXXI (281) I’m Not Quite Sure Why

CCLXXXII (282) An Incessant Murmour

CCLXXXIII (283) Familiar

CCLXXXIV (284) A Bit Like

CCLXXXV (285) Lyme Regis

CCLXXXVI (286) On A Sunny Day

CCLXXXVII (287) So, Farewell

CCLXXXVIII (288) Yee-Hargh

CCLXXXIX (289) Um,

CCLXXXX (290) Hoist It High, Okay?

CCLXXXXI (291) See You Soon

CCLXXXXII (292) And Remember

CCLXXXXIII (293) One Thing

CCLXXXXIV (294) And One Thing Only

CCLXXXXV (295) It Doesn’t Matter

CCLXXXXVI (296) Schaden

CCLXXXXVII (297) Freude

CCLXXXXVIII (298) Get Ready

Tell me about making work on top of photographic images…

The photos are either ones that I have taken, belong to the Penke archives or are stills from afternoon matinees. I love photography but I’d never made photo-etchings before and Alan Smith taught me the process before his retirement. It was only in my final year that I worked out how to combine photo-etching with hard-ground drawing and aquatint – I’d built the bridge!